Artifical Intelligence is Pioneering Advances in Ecology

The GitHub repo for this project can be found at: https://github.com/TristansCloud/YellowstonesVegitiation

“Remote sensing is the acquisition of information about an object or phenomenon without making physical contact with the object… [and] generally refers to the use of satellite or aircraft based sensor technologies.”

It’s the lazy persons data collection. The ‘scan the entire world every day’ data collection. Remote sensing has given us a continuous stream of data on the state of the world, revolutionizing agriculture, international defence, environmental monitoring, crisis management, telecommunications, weather forecasting, firefighting, and many other fields. Any application that can be framed in a spatial context has likely benefited from advances in remote sensing.

As an ecologist, my field has been able to monitor global forest cover change and harmful algae blooms, estimate populations of endangered species, and designate the areas most important for ecosystem functioning to be protected all through the use of remote sensing technology.

Not wanting to be left out, I’ve been thinking about what remote sensing can bring to my own research interests. I study the processes that drive evolutionary change at the intersection between evolutionary biology and ecology called eco-evolutionary dynamics. I am particularly interested in the non-living factors that structure an ecosystem: how does the intersection between terrain, climate, geochemisty, and human disturbance (technically a living factor, but a special case) determine what organisms will be living there?

I am also very interested in machine learning solutions and applications of big data. A question naturally arose, can I use remote sensing and machine learning to link my non-living predictors to the resulting ecosystem at a large scale and across different ecosystems types?

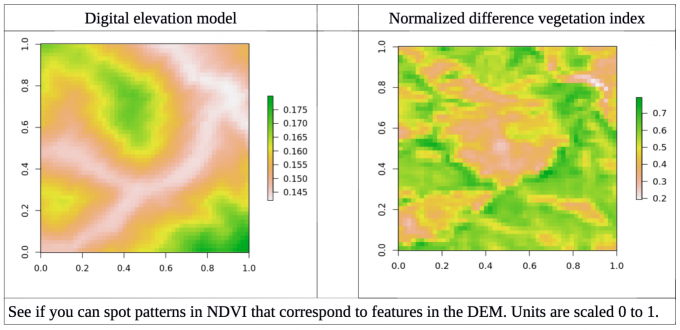

To do this, I first had to define my predictors and response variables. To start simple, I chose myresponse to be open source NDVI images from the Landsat 8 satellite, which photographs the majority of the globe every 16 days. NDVI stands for normalized difference vegetation index, a measure of how much vegetation is in a given area. Plants absorb photosynthetically active light and reflect near infrared light, so the difference between these two wavelengths is a measure of how much healthy plantmaterial is present. I chose my predictor to be a digital elevation model (DEM) and ignored climate, geochemistry and human activity at this first attempt. I selected an area to study that should have little deviation in climate across the study area, as to start I only wanted to focus on terrain affects on the first try at building this model. However, I wanted to design a data pipeline that could easily be expanded once I wanted to address more complex predictors and responses.

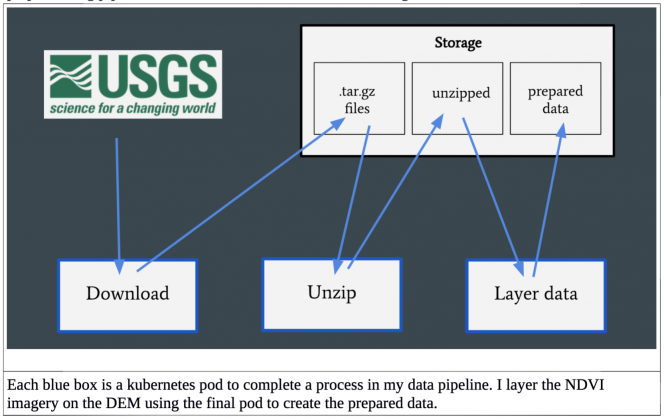

Kubernetes provided an ideal solution, allowing me to create pods to complete each step in my preprocessing pipeline and delete those resources when no longer needed.

The USGS hosts an API for downloading Landsat 8 images, which I accessed through the programming language R and was executed in the download pod. The data was then unzipped in a new pod, and finally my predictor DEM was layered on the NDVI image in a final pod to create my prepared data. This final step is easily expandable to layer on different predictors as I expand the project.

Neural Networks

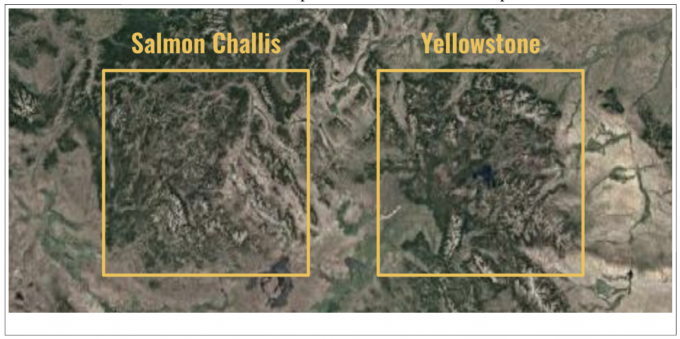

The hypothesis I wanted to test for this analysis is how well can I predict vegetation growth from a DEM, and how transferrable that model is from one area to another, assuming climate and other factors stay the same. To test this, I downloaded NDVI images from two national parks in the Northwestern USA: Salmon Challis national park and Yellowstone national park.

I chose these two places as they are in a similar geographic area so likely have similar climates. They also are both mountainous regions and cover similar amounts of land. Finally, they are both national parks and should have pristine ecosystems relatively removed from human interference (although there was some agriculture and human settlements in both areas).

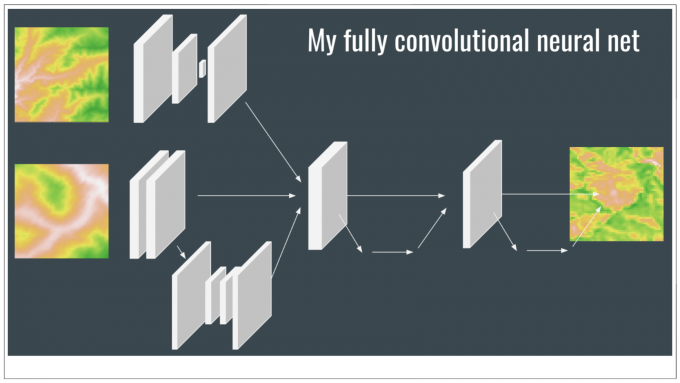

I selected two scenes, one from Salmon Challis and one from Yellowstone, from the same year and season. My plan was to build a fully convolutional neural net (CNN) and train it on tensors from Salmon Challis to predict tensors in Yellowstone. By taking 51 pixel by 51 pixel sections of the NDVI and DEM images, I created 17,500 individual tensors for Salmon Challis and 17,500 individual tensors for Yellowstone. I then built a CNN to take two inputs, the 51 x 51 DEM as well as a 51 x 51 pixel low resolution DEM that covered a much larger area, in case the large scale geographic features surrounding an area are important to predicting vegetation. The output of the model is the 51 x 51 pixelNDVI image.

Through trial and error I found that an inception framework, inspired by GoogLeNet, improved the stability of model predictions. Inception branches tensors into separate processing pathways, possibly allowing models to understand different features in the data all while maintaining a computationally efficient network. GoogLeNet won the ImageNet Large-Scale Visual Recognition Challenge in 2014 with this style of architecture, and I recommend reading the original research paper (which is not overly technical) of this and other models if you are interested in learning more about network architecture effects on neural network performance. UNet, a separate convolutional network, also inspired some of my architecture.

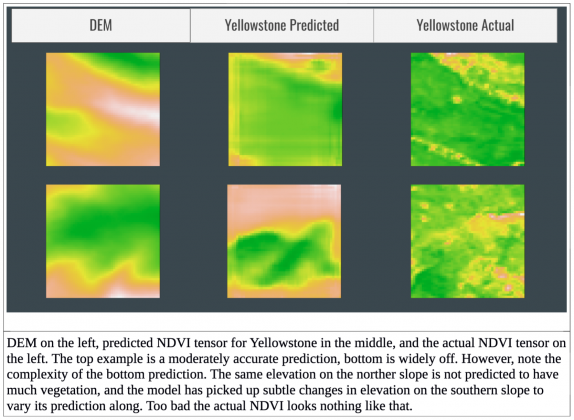

Overall, the model performance surpasses a classic technique based on generalized additive models (GAMs) but is still unsatisfactory, getting quite a few images wrong. See the final figure for some of the model predictions. I wanted to teach myself to design neural networks, so for now I am avoiding transfer learning from a pretrained network although this is still an option. Through GCP, CloudOps, and the huge amounts of remote sensing data generated daily, I have the resources and data to improve this model. I would love to pass many more predictors, and increase the width and depth of my neural network. Take a look at my github if you would like to see my actual layers in the neural network or the Kubernetes solution I use to download data. I’m still working on this project, so my network architecture may have evolved a bit. Good luck in your own data science adventures!

Kubernetes and cloud native technologies have allowed scientists to store and make sense of the data collected by remote sensing. Nonetheless, these technologies can be difficult to learn and master. CloudOps’ DevOps workshops will deepen your understanding of cloud native technologies with hands-on training. Take our 3-day Docker and Kubernetes workshop to get started using containers in development or production, or our 2-day Machine Learning workshop to make your ML workflows simple, portable, and scalable with Kubernetes and other open source tools.

Tristan Kosciuch

Tristan is an evolutionary biologist interested in the effects of landscape levels on genetic and phenotypic variation. He works in Vancouver Island on threespine stickleback and in the Lake Victoria basin on Nile perch and haplochromine cichlids. His work on stickleback uses remote sensing to quantify environments to test the predictability of evolution.